Nikki Johnson has made a habit out of challenging the system.

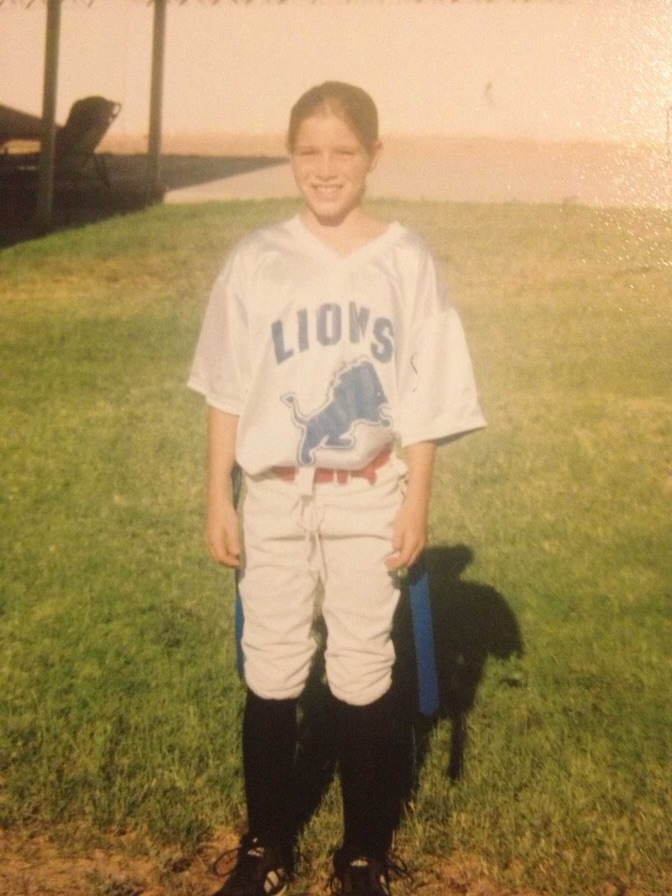

At the age of 10, the only sport she was interested in playing was flag football. Her hometown of Henderson, Nevada, didn’t have a girls league so she played with the boys.

Other girls eventually joined the team, and two years later there were so many who wanted to play that Nikki started a girls division with help from her parents and coaches.

“It was important we had our own so we could shine on our own,” she said. “There were too many girls that were good at this game and wanted to play for us not to have our own division.”

With Nikki leading her team as quarterback, the girls went on to win three regional and two national championships.

That was just the beginning of Nikki’s fight for women’s football.

When she was in high school, her school district needed to offer a new girls sport to become compliant with Title IX, so she and her parents advocated for flag football. It was added as a club sport for several schools in 2009, and a few years later became a varsity sport for 37 schools in the district, where it’s still being played.

Nikki’s childhood experiences had taught her that making waves and fighting for what’s right can lead to systemic change. But she would soon meet a more formidable obstacle: the Lingerie Football League (LFL) and its founder, Mitch Mortaza.

Nikki was 20 years old and playing women’s tackle football for fun when she learned about an opportunity to turn her passion into a profession: The Lingerie Football League was holding tryouts in Las Vegas and word was they could pay their athletes.

It was not at all what Nikki expected.

“I went to the local tryout and I thought it was a joke,” she said. “The guys who were the coaches at the time, they seemed like they knew nothing about football.”

Between the apparently inept coaches and the uniforms that were more revealing than some bikinis, Nikki didn’t think it was a serious opportunity. Plus, she had learned that the gig wasn’t going to pay a living wage.

“I was like, ‘I’m not playing for these people,'” she said. “I walked out.”

A month later Nikki got a call from her former tackle football coach, a man she respected and trusted. He told her that he would be coaching the Las Vegas Sin for the Lingerie Football League, that the coaches she had met had been fired and that he needed an ace quarterback.

“He was like, ‘Look, I need a quarterback. Just come out here and we’ll do it our way. We’re gonna do this our way we’re gonna play real football,'” she remembers him saying.

“And that’s exactly what we did,” she continued. “We didn’t go out there and just put on some show. We went out there and played legit football.”

Outside of uniforms that pushed up their breasts and revealed their buttocks, the Lingerie League players looked every bit like traditional football players, complete with fans in the stands and cameras capturing the action.

In one game against the Chicago Bliss, Nikki threw passes and handed off the ball with the confident ease of Peyton Manning.

“Touchdown!” yelled an announcer after one of Nikki’s passes soared into her teammate’s waiting arms in the end zone.

On another play, Nikki’s teammate tackled an opposing player who had run for a long pass.

“I was fucking out, you fucking bitch!” the opponent screamed. A couple minutes later, she was doing a dance in the end zone after scoring.

“It was a ton of fun,” Nikki said. “I was in my early 20s, and being able to play a sport that I loved and to travel doing it … that was really awesome.”

Nikki built a bond with her teammates and loved working with her coach. The best times, she said, were when the team traveled to Canada, Mexico and Australia to play.

In the U.S., with the Lingerie League was footing the bill, travel meant red-eye flights, waiting around all day for photo shoots, playing a game and flying back home the same day. The audiences were modest and the pay was $0, Nikki said.

For the foreign travel, she said companies partnered with the Lingerie Football League and paid for the women to play exhibition games in elite venues in front of huge audiences. Because the companies and not the Lingerie League were paying, she said the women would get roughly $500 a game.

“Those were some of the most fun games that we played, in front of 20,000 to 30,000 people,” Nikki said. “It was nuts. We played in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City, and then the Allphones Arena (currently the Sydney SuperDome) in Sydney, Australia … Those are memories, those are opportunities I would never would have gotten without LFL. They made us feel like pros for the first time.”

Although the highs were high, they weren’t enough to offset the lows that Nikki and some of her fellow teammates experienced with the league.

They were spending hours upon hours every week practicing, doing photoshoots, going to other promotional events and playing, all with little to no pay. They were forced to wear barely there uniforms with minimal padding and hockey helmets, which aren’t built to withstand football-style tackling but were perfect for showing off the players’ attractive faces.

The inadequate equipment meant worse injuries on the field.

Nikki recalls one of her friends on an opposing team took a knee to the helmet during a tackle. The hit cracked her face guard and shattered her cheekbone.

Nikki was badly injured herself in one of the last games of her LFL career when she took an illegal hit to her neck and head.

“It took me right off my feet,” she said. “I was rushed to the hospital … It was bad whiplash and I was sore for a while.”

Nikki doesn’t remember too much about the hit and the ride to the hospital, saying “when it happened, it was just fast and I was scared.”

“I obviously didn’t want it to be something that would affect me long-term,” she said. “Then afterwards I was just angry and knew things needed to change.”

Nikki wanted to fight for better helmets designed for high impact. So she started trying to round up other players who’d been hurt to discuss safety issues and the lack of pay.

“I tried to band a lot of the good athletes together and when Mitch Mortaza caught wind of that, I got text messages from him cussing me out and throwing me out of the league,” she said.

Nikki’s career in the Lingerie League was over less than three years after it had started. A decade later, she still misses her teammates and what they were building.

“I’ve played football since I was 10 and I played with some of the best athletes I’ve ever played with” in the Lingerie Football League, she said. “I loved playing with all those girls and we took it very seriously but he just took advantage of everybody.”

Even though she no longer had a team, Nikki continued to fight for her teammates, their safety and their right to fair compensation.

In 2014, Nikki filed a federal lawsuit against Mortaza and the Lingerie Football League, alleging failure to pay the required minimum wage or overtime. She was the only named plaintiff in the class-action lawsuit but at least six other players joined her in writing declarations describing the conditions under which they had played.

“At times, Mortaza would attend the practices to oversee our training. These were known as ‘preview checks’ or ‘fat checks,'” wrote player Heather Perez, who played for the Philadelphia Passion between 2009 and 2013. “We were told the training exercises we should do, and that we would be out of the league if we did not do them and got ‘fat.'”

“Those players would be required to send ‘picture updates’ to Mortaza every two weeks, ostensibly to show they were losing weight,” wrote Melissa Margulies, who played on the Los Angeles Temptation from 2010 to 2013.

“Failure to abide by these terms would result in expulsion from the league,” she continued. “In fact, if players even asked a question about why they were singled out for the ‘picture updates,’ Mortaza would term that ‘talkback’ and expel the player from the league.”

The women also described the hours they worked for no pay, and having to sign non-negotiable contracts that required them to pay $45 to register to play, report promptly for all games, practices, and promotional, and media events, and prohibiting them from organizing, striking and objecting to any “accidental nudity” during games, among other clauses.

Although the contract stipulated that the women would be paid a portion of ticket sales, they say that happened only sporadically. The most Perez said that she got, for instance, was $150 one season.

Not only was the pay minimal to nonexistent, the players had to provide for their own medical insurance and foot any bills from injuries, they said.

Lauren LaBella, who played for the Philadelphia Passion and the Baltimore Charm from 2009 to 2014, said she was injured three times during her career.

“During a game, an opponent’s knee hit my face, which caused my nose to break,” she said. “The LFL did not provide me with adequate medical treatment. I was required to pay around $7,000 out of my own pocket for surgery. I also paid around $1,000 for physical therapy for my left ankle, which I fractured during practice … Additionally, I sustained three hairlines fractures in my left shoulder during practice, because the coach did not permit us to wear shoulder pads.

Consequently, I paid for X-rays, MRI scans, and cortisone shots, which totaled around $2,000.”

The women say they were prohibited from wearing football-style helmets, shoulder pads and other gear because they obstructed views of their bodies and faces.

“When players questioned the safety of this, Mortaza specifically stated that this was to allow fans a better view of the players’ faces. Players are required to wear their league-issued shoulder pads positioned so that fans can see their chests,” Margulies said. “Mortaza also banned the use of shoulder straps worn by some players to prevent shoulder injuries. Failure to abide by any of these attire regulations would mean discipline, up to and including expulsion from the league.”

Mortaza never showed in court to deny the allegations, nor did anyone from the league or a lawyer representing them.

In 2020, Nikki won the case by default, with the court awarding her more than $1 million and ordering for attorneys fees and costs totaling more than $130,000.

It was a hollow victory, she said.

“We still have yet to receive any money from the lawsuits,” Nikki said, referencing her legal action and a separate one in Los Angeles court filed by Margulies.

But it’s not about the money, she said.

“It was really about saying, ‘Hey, he’s doing some illegal toxic shit here. And let’s talk about it so that we don’t have more generations of girls that are gonna get wrapped up in this stuff like this.’ Like, we need to be able to stand up and say, ‘This is wrong. There are better opportunities.'”

It would have been a more satisfying win, she said, if Mortaza had been in court.

“It just felt like forfeit,” she said. “Especially since nothing happened afterwards, there were no repercussions for anything … It just felt like nothing really happened.”

Though Mortaza didn’t answer to the lawsuit, he has given various interviews over the years defending the league.

When asked by CNBC in 2009 what the women in the league would be paid, Mortaza responded:

“That’s the best part of it. There is no salary,” he said. “The players get a percentage of the gate based on them winning and losing. There’s a big discrepancy between those percentages. The players are going to be incentivized to play fierce football and win games.”

As for people who said the league exploits women, Mortaza told the Spotlight Report in 2012 that such opinions are “developed prior to them watching LFL football or knowing its athletes.”

“Simply put, they are judging the book by the cover instead of its substance,” he said.

Mortaza told the Palm Beach New Times in 2010 that comments about the league being exploitative are “a knee-jerk reaction.”

“It’s completely understandable, but I can assure you, I’d put my very expensive mortgage up in Hollywood that they’ve never seen a game,” he said. “If you see a game, you’re not going to come to that conclusion. These women come from all walks of life. They’re confident. We have an 85 percent college graduate rate. I put that against any men’s league.”

In a more confrontational interview about the league’s physical standards, Australia’s Studio 10 asked Mortaza about allegations by then-18-year-old Micaela Parrot that she was told she was too big to play in the Australian Lingerie Football League.

The show’s hosts grilled Mortaza about the claims and why Parrot couldn’t play in the league when she was clearly an athlete.

“Anybody that knows the LFL, that’s followed the LFL, knows the rigorous workouts in the offseason, in season, that our athletes go through,” Mortaza said. “And through those workouts, they mold into a certain athletic body type. And we just felt that Miss Parrot wasn’t at that level at this point in terms of physical fitness, and that’s the reason she couldn’t compete at that point.”

One of the hosts pushes back, telling Mortaza that Parrot can run 10 kilometers, bench press 100 kilograms, and “looks pretty much like any other linebacker.”

Mortaza responds by saying “a Japanese Sumo wrestler would not run track and field.”

“It’s a different body type,” he said. “Our sport is very different from the NFL. It’s very fast-paced. Most of our athletes play both offense and defense. You have to be in incredible cardiovascular shape. So there’s no ill will, there’s nothing personal against Miss Parrot. I frankly don’t even know her. That wasn’t an issue here. The issue was she wasn’t the athletic fit that you need to be to play the LFL game.”

The hosts later pressed him about what body types he looks for in players, with one of them saying: “So what? Abs and fake boobs is what you’re after?”

“I take offense to that,” Mortaza said. “I’m sure our athletes across Australia will take offense to that. You’re obviously making that point because you don’t know the athletes, you don’t know the sport … They’re all former high-level athletes, and they love the sport they’re playing in, and I don’t see why they’re being faulted for that or attacked.”

These days, women are still playing for Mortaza, they’re still wearing skimpy uniforms and wearing field hockey helmets. The league has been renamed the X League and now football legend Mike Ditka is serving as its chairman.

“When I thought about who could be the one central figure that can tell our story in the X League, that previously played or coached, that really instantly would send the message that look, this is serious, they’re going to take this seriously, somebody that’s blue collar that exudes the game of football, and there is no bigger figure than Iron Mike Ditka, and we’re very proud to have you on board for this journey, Coach,” Mortaza told Ditka in an interview posted to YouTube.

Ditka told Mortaza that he wanted to get involved because women deserve to play football.

“These girls are tough and they want that opportunity to play,” he said. “Why not give it to them? … The football thing, I think it will work out good for women, I really do. It’s gonna be now, with the X League.”

It’s unclear whether the women currently playing in the league are being compensated.

As for Nikki, she said she won’t be watching.

“I went through a lot with the league. I had some highs and some hopes and dreams with it,” she said. “I did it for the love of the game, and I wanted to make that passion something I could get compensated for because I thought I did it well enough to do so. A lot of other girls felt the same. We were like, ‘Hey, this is something that’s on a big stage and I’m good at it. I’m an athlete.’ And he was the kind of guy who was just kind of dangling the carrot out there and just kept putting it further every time we got close.”

Still, she said she’s thankful for the good times she had.

“I wouldn’t say I wouldn’t do it again,” she said. “I would totally do it again. But we could have been treated better.”